Reflecting on Strike Fast, Dance Lightly

Strike Fast, Dance Lightly is an exhibition of artists who have taken their cues from the imagery and accoutrements of boxing, not as sport but as metaphor for the physical and emotional battles waged over the demands of our spirit and our minds. It is a show of gilded darkness: a light filled arena, full of brute force and dark materials. This is a show by artists who’ve answered the bell and made art that asks each of us; What are we fighting for? What is worth fighting for? Pulling no punches, this show is poignant, powerful, rough and tender, full of creative raging.

A Meditation on Strike Fast, Dance Lightly by Eric Fischl

This old bronze boxer, bruised and cut, is still sweating. He has come to the end of his fighting life or just past it. He looks over his shoulder, looks back, hears voices callimg out of his corner, calling him back. Cornered. Punch drunk. Exhuasted. Knows only what he knows.

The Pugilist at Rest

In the clearing stands a boxer

And a fighter by his trade

And he carries the reminders

Of every glove that laid him down

Or cut him till he cried out

In his anger and his shame

”I am leaving, I am leaving”

But the fighter still remains

PAUL SIMON - The Boxer

The old artist stares into his bathroom mirror. Harsh yellow light captures and silhouettes his shadowed head, painted the color of dried blood. His fists are clenched, arms splattered red, bruised and beaten by the paint that created him. He has portrayed himself not as an amateur but inept. He’s fought against the perfection that taunts and eludes him. It is the life of the artist whose time was spent shadowing-boxing demons.

Bonnard’s Le Boxeur (portrait de l’artiste)

Your faith was strong but you needed proof

You saw her bathing on the roof

Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew ya

She tied you to a kitchen chair

She broke your throne, and she cut your hair

And from your lips she drew the Hallelujah

LEONDARD COHEN - Hallelujah

Strike Fast, Dance Lightly is an exhibition of artists who have taken their cues from the imagery and accoutrements of boxing, not as sport but as metaphor for the physical and emotional battles waged over the demands of our spirit and our minds. It is a show of gilded darkness: a light filled arena, full of brute force and dark materials. This is a show by artists who’ve answered the bell and made art that asks each of us; What are we fighting for? What is worth fighting for? Pulling no punches, this show is poignant, powerful, rough and tender, full of creative raging.

Strike Fast, Dance Lightly is about weight class. It is the heavy weight of responsibility that comes with accepting the truths in our lives. Acknowledging the rules of the game without accepting its limitations, this is art that does what art is supposed to do: it points us in the direction of higher purpose.

The art works in Strike Fast, Dance Lightly reveal what it means to stay open, honest and in touch with our vulnerability, accept the risks we are willing to take to learn who we are, and the bravery to go toe to toe to face ourselves.

-ERIC FISCHL, 2023

Heaven on Earth: Sally Gall’s New Photographs

Though my meditation on Sally Gall’s new body of photography, which involves kites and clotheslines, is not about painting, nonetheless I must start there. I’m starting at that moment in art-historical time when photography usurped painting’s authority as arbiter of direct and verifiable observation.

Sally Gall, Turbulence, 2015

Though my meditation on Sally Gall’s new body of photography, which involves kites and clotheslines, is not about painting, nonetheless I must start there. I’m starting at that moment in art-historical time when photography usurped painting’s authority as arbiter of direct and verifiable observation.

To some painters, this moment of usurpation meant liberation, freeing the hand and the eye to look elsewhere for truth. To others, it was condemnation and relegation to a diminished status – a life of effort they no longer needed to exert.

Ironically, the liberation of painting from the constraints of “objective” reality, which allowed it to move away from the surface of things and into a deeper and more abstracted “feeling” realm brought painting literally back to the surface. Painting became first and foremost about paint.

Several years ago I visited Monet’s home in Giverny, France, the site of so many of his greatest contributions to the history of art. This is the place where he finally got rid of the horizon line and let the water lilies scatter across the surface of the painting to become compositional and tonal markers on an inflected surface of paint. This is where Monet almost gave up trying to capture detail.

His estate has tried diligently to recreate his famous garden so that when walking through it you can crop your sightlines in ways that give you the impression that you are witness to his moment of inspiration. I stood before his iconic pond, full of its blossoming water lilies, anchored at one end with his oft-painted Japanese footbridge. I stared. I squinted. I cupped my hands beside my eyes to block out peripheral distractions. I could see what was there. I could see what he chose to paint. What I could not see was what he saw.

If you are too tethered to the practical eye, the familiarity of objects stand no chance of becoming inspired, animated, fantastic and strange; no chance for transformation.

A principle difference between painting and photography, when artists reach to capture the essential shapes and colors that will push their perception towards abstraction, is that painting breaks free while photography always includes the origins of its source.

One could argue, rightfully, that the transformative experience in art is more difficult to achieve through photography because it is always moored to its own banality.

So when a photographer is able to achieve an ecstatic and animated transformation from what, until that photograph was made, had passed as unremarkable, you have to acknowledge that that photographer is not just skilled but truly gifted.

Sally Gall has always been interested in waves and caves, caverns and curls, folds and furls. In her most recent work, she continues to express her delight and pleasure in the sensuality of form, specifically the flickering of things in the breeze.

This book, Heavenly Creatures, weaves together two stories, both having to do with wind, air, and colorful shapes, but to this she brings a new perspective: these stories can only be seen from below.

Kites on strings and clothes on clotheslines appear as abstract shapes set against a ground of blue, luminous yet flat. Sally has done for laundry and kites what Karl Blossfeld did for plants: transcend their natures while absolutely adhering to them.

Let me change the subject. (As I said, this is a meditation so I allow it go where it pleases.)

There are two kinds of art making, paradoxical in their oppositions but contained within the creative mind. An artist is generally predisposed to one or the other. On the one hand, you have art seeking to resolve pain, torment, injustice, emptiness, and conflict through truth-telling. On the other, you have art that blatantly disregards that suffering.

During WWll, while Matisse painted the sensuous glow of the Mediterranean sea and sky, the color saturated folds and patterns of an odalisque’s garment, and the curves of her glowing skin, his wife and daughter were picked up by the Gestapo for questioning. I put it to you to tell me which painting he was working on at that time of this grave interruption.

Clearly, either Matisse did not feel that stress and worry or the darker emotions were not the best fuel for his inspired practice. He had his eyes set on the distant horizon: the site of ultimate conflict-resolution. Through the lightness of his touch, the light of his color, the eroticism of his fluid lines, he delivered to us a near-heavenly pleasure that carried us out of the temporal, out of our suffering, out of ourselves.

Sadly, I am not that kind of artist, but Sally Gall is. In these dark days of American existential conflict and crisis, where anger and fear are running fast and burrowing deep, it has to be seen as an act of bravery to turn one’s attention away from the flame and focus their net on capturing the elusive distractions of fleeting beauty.

From Zbigniew Herbert’s poem, Ornament Makers, I take these few lines because it is in these lines that the significance of Sally Gall’s art is most eloquently expressed.

Praised be the ornament makers

the masons and the decorators

the creators of flitting angels…

the poets it goes without saying

the defenders of children playing

giving voice to smiles hands and eyes

they’re right it is not art’s business

to seek the truth is for science

masons guard the heart’s warmth

Eric Fischl

Sag Harbor, NY.

Meditation Through a Windshield

I had not seen nor known of Matisse’s painting, The Windshield, until a few years ago. It is a painting depicting a landscape seen through the windshield of a car of a country road lined with trees. In the foreground, propped against the steering wheel, is a sketch pad.

Henri Matisse, The Windshield, 1917

I had not seen nor known of Matisse’s painting, The Windshield, until a few years ago. It is a painting depicting a landscape seen through the windshield of a car of a country road lined with trees. In the foreground, propped against the steering wheel, is a sketch pad.

Looking at this painting, I realized that the car interior was, at that time, a truly new kind of interior space.

Art is about seeing. The history of art-making can be understood as the artistry with which an artist constructs the space an object occupies, or draws the viewer into that space to create a meaningful experience. The choice of space is not arbitrary. Where has the viewer been placed? From what vantage point are you seeing what is being depicted? In the case of this Matisse painting, you are in the driver’s seat. You are seeing the world through the artist’s eyes.

At the time this painting was created, the car was still very much a new thing, both in its technical advancement and in our relationship to it. It had not fully replaced the horse or the horse-drawn vehicle. It was rare enough to still be a curiosity; a novelty whose significance had yet to be understood for the impact it would come to have on us.

The arc of the car’s depiction is a bell curve whose baseline is its velocity. Depictions quickly ascend the arc as more and more artists used its image to capture speed as a symbol of new-found power. Along with speed, the car becomes a celebration of technological and design advancement with all its promise of a brighter future. As it achieved its status as a symbol of manliness, sexiness, wealth and class, this vehicle moved swiftly to the very center of our lives.

Art of the car has adroitly captured the effects of what advertising has sold us.

In the mid-1960’s, the car crash as subject matter was introduced into the lexicon of car depictions. From that point forward, like all things fossil-fueled, gender-stereotyped, and class-based, the awareness of the car’s impact on us and on the planet has created a profound ambivalence toward this machine which is at the center of our lives. What began as a curiosity has become a struggle to articulate and resolve the ambivalence we have toward the our love, hate, anger, pleasure, fetishistic attachment, camaraderie, masculinity, class, wealth and dependence we have with the car.

Prior to the car, the driver, along with its source of power (horse, ox, donkey), was always external to the cabin. Drivers sat on top, sat in front, or walked beside it. Although the power source is still external, the design of the car placed the driver inside the capsule, along with passengers and cargo. The word “automobile” acknowledges that our relationship to vehicles has changed significantly. Auto- as a prefix indicates an attachment of the “self” to the object. By bringing the “self” inside the car, the interior becomes a profoundly intimate space, metaphorically mirroring our mind/body relationship. Like our mind trying to negotiate and navigate our bodies in relationship to others, so too the car. This fundamental investment of self-identity into the car is why our relationship to the car is so complicated. Now, with our growing awareness of the negative impact this machine is having on our own survival, how do we extract what is positive from what can no longer be sustained? The pressing question for us these days is: how do we disentangle our identities from this powerful mechanical exoskeleton?

– Eric Fischl

Thoughts on Sag Harbor in Focus

For the last five years, working closely with art teacher Peter Solow, students studying photography at Pierson High School have been asked to create work that explores various photographic genres using Sag Harbor as their muse. The result of this exercise has culminated each year in a juried exhibition called Sag Harbor in Focus, which has been shown at various venues in the Village (Dodds & Eder, the Whaling Museum, the John Jermain Library).

Photo credit: Michael Heller, Sag Harbor Express

For the last five years, working closely with art teacher Peter Solow, students studying photography at Pierson High School have been asked to create work that explores various photographic genres using Sag Harbor as their muse. The result of this exercise has culminated each year in a juried exhibition called Sag Harbor in Focus, which has been shown at various venues in the Village (Dodds & Eder, the Whaling Museum, the John Jermain Library).

Sag Harbor in Focus was meant to encourage the local kids to see where and how they live with fresh eyes, to re-examine and question what they’d taken for granted or had overlooked. This is the discipline of artmaking and the engine of creativity. Simply put, art transforms the local into the universal through the lens of the gifted eye.

This is the first year that April and I have been able to exhibit their work at The Church. It has been a year of Covid and quarantine. Sag Harbor, as muse, got a whole lot smaller and a whole lot more local. Our lives have all been affected by the fear, anxiety and isolation this pandemic has caused. We had to go indoors. We went inside ourselves. But through this uncertainty, this sudden and unforeseen change of plans that forced us to jump start our resourcefulness, determination and resilience, we found out a lot about ourselves, our families, our neighbors and our friends.

What is so uplifting in seeing this exhibition, is that in this most extraordinary of times, the Pierson photographers did not suddenly go blind. They did not shy away from harsh truths. They did not shut down. They steadfastly documented the moment we are all living through with their eyes clear and wide open.

In these wonderful photographs, both individually and collectively, you see an eloquence and courage in their acknowledgment that the world and their town had suddenly become terrarium-like, microcosmic, and sometimes lonely. These photographers have reduced the language they used to describe it, becoming a world of nouns; the bed, the dog, the table, the computer screen, the book, the window, the mask, the eye, the shadow and the light. And with this reduced language they have captured and expanded how we can understand not only what they have been dealing with but what we all have gone through in this terrible crisis. And this is the true nature of art.

Shout-outs go to Pierson Faculty members, Peter Solow and Liz Cataletto, for their inspired teaching and dogged determination to keep all heads above water, to the Reutershan Foundation, to Ray and Carol Merritt’s Cygnet Foundation for their financial support, and to Mary Ellen Bartley for her trained and judicious eye in making the selection of works and awarding the winners. It has been a celebration of a real achievement.

– Eric Fischl

Meditation on Kerry James Marshall's Untitled, 2008

Painting is a language. Besides being seen, it is meant to be read and to be felt.

As a painter, I have to believe that everything that I put into a work will be transmitted to people who experience the painting in the flesh, so to speak.

Kerry James Marshall, Unititled, 2008, Acrylic on fiberglass, 79 x 115.25 in. Collection Neda Young

Painting is a language. Besides being seen, it is meant to be read and to be felt.

As a painter, I have to believe that everything that I put into a work will be transmitted to people who experience the painting in the flesh, so to speak.

Great art captures and binds emotions with metaphor, eloquently expressed through details of observation.

The grace of a great work of art is that it doesn’t feel forced or labored.

Kerry James Marshall is clearly a master. His large, untitled work from 2008 is on display April 15 – May 15 at The Church as part of a conversation between a photographer, a poet and a painter. The show is called In Dialogue: At the Edge of the Sea.

I am going to focus on the Marshall painting. Because the work is untitled, there affords me more freedom for my interpretation. Because of how beautifully and confidently he has painted it, I am seduced by its unfolding.

The painting depicts a scene taking place at the edge of the sea. A couple, silhouetted against a sunset (or sunrise… or both?) look off to the distant horizon. They lean into each other, shoulder to shoulder, head against head, body to body in an intimate and comfortable embrace. His hand gently caresses her bottom. In the darkness of their silhouette there is no space between them. They are indivisible. They are a union.

A ship sails to the horizon. A tiny lighthouse shines its beacon towards the immensity of the sun’s heavenly light. The ship-bow shape of land on which the couple stand reinforces the painting’s theme of journeys: arrivals, departures, returns. This painting invites reflection on the significance and impact different journeys have upon us: coming from, escaping to, longing for return, or with the history of slavery, taken from. This painting asks us to recall or imagine how the experience of any and all of those conditions would shape our souls.

There is an old broken down barbed wire fence, the remains of which run up and over one side of this spit of land. It denotes borders, boundaries, edges or separation. The barbs explicitly warn us to keep out. There is dune grass and daisies? sparsely dotting this hardscrabble plot of soil. They feel tough, resilient, willful and as far as the daisies are concerned, out of place. These daisies appear in shadow on the lower right and move in single file, sneaking under the fence, until, in the warmth and encouragement of the sunlight, they spread out and flourish.

It should be noted that the daisy has historically and mythologically been used as a symbol of innocence, childbirth, motherhood and perhaps most importantly, new beginnings.

Seagulls flap and flit above the couple’s heads. One of the gulls transects the sun, splitting a beam of light into two halos. This image suggests that this painting is meant to be understood as a sacred allegory of reassignment and redefinition. The seagull’s totemic significance is cunning, perseverance and survival.

The time of day is fixed at a point of eloquent ambiguity. Frozen at the precise moment when a sunrise and a sunset can share the same tone of light and the same position of the sun to the horizon but not share the same significance. This gives the scene a wide range of interpretive direction. Depending on how one reads this moment of time, the painting will be understood as a hope-filled moment or a scene of longing and loss.

I seek out art looking for meaning beyond appearance. I want to leave it feeling as if I’ve seen an apparition, knowing I’ve seen something remarkable. This Kerry James Marshall painting more than satisfies those criteria.

– Eric Fischl

Venus Looks Back

It’s the look - the look in her eyes. It’s not a stare but it is direct. It is perceptive, even penetrating. It shows her to be a conscious being capable of scrutinizing the world as the world scrutinizes her. She does not smile. She demonstrates no need to mollify us. She knows she is looking and she knows that she is being looked at. She knows that the camera is the gateway to a subsequent anonymous audience of countless lookers whom she cannot see but knows will be there, looking at her in the future. She knew you would look. She knows that the looking will never stop. It’s part and parcel of the work that day, on those rocks, in that bathing costume, under that sky, in front of those waves.

Awol Erizku, Teen Venus, 2012, Digital chromogenic print in custom maple, 22 Karat gold leaf frame, Collection Glenn and Amanda Fuhrmann, NY, Courtesy of the FLAG Art Foundation

It’s the look - the look in her eyes. It’s not a stare but it is direct. It is perceptive, even penetrating. It shows her to be a conscious being capable of scrutinizing the world as the world scrutinizes her. She does not smile. She demonstrates no need to mollify us. She knows she is looking and she knows that she is being looked at. She knows that the camera is the gateway to a subsequent anonymous audience of countless lookers whom she cannot see but knows will be there, looking at her in the future. She knew you would look. She knows that the looking will never stop. It’s part and parcel of the work that day, on those rocks, in that bathing costume, under that sky, in front of those waves.

This photograph was taken nine years ago. Her life has moved on. The look declares that there is a difference between looking and knowing. They are not the same thing. The image and the person are never identical. Yet, that is the Barthesian magic of photography. It freezes a moment, and often an individual, for eternity and allows an unconnected person - you, dear viewer - to make up a story and feel a personal connection with this image, this subject, this scene.

So what draws you in? The composition is balanced even though she stands not in the exact center of it. The harmonious palette of cool blues, greens and grey of the rocks, sea and sky foregrounds her and complements the warmth of her skin, the red in her hair, the gold of her bathing suit, the coral of her nail polish. She is beautiful. She is young. The title, Teen Venus, links her to a tradition of European art going back to the Renaissance that idealized female body as something divine, especially in conjunction with nature. In 1863, Édouard Manet turned the tables on that long and condescending trope with his painting Olympia. That work hinges on the calculating look of a worldly woman, lying naked on a bed. She knows her worth, her place in society and, most importantly, she knows that you are looking at her. There is no place for your voyeurism here. She sees you and stares back, holding your gaze. She is clothed by her knowledge of the rules of the game.

Born in Ethiopia and raised in the South Bronx, Awol Erizku is used to contrasts and hyphenated experiences. His work explores the liminal spaces between cultures, lives and aesthetics. Teen Venus was created as part of a series of work shown in his first solo exhibition, Black and Gold, which was held at the Hasted-Kraeutler Gallery in 2012. It featured staged portraits of African American subjects that updated poses and scenes drawn from iconic images from Western art history and re-contextualized them using everyday environments and contemporary objects. This fusion of European art, vernacular accessories and fetishized artifacts of African culture has become a staple of Erizku’s photography, sculpture, and video installation that counter the absence of people of color in the canon of art history. His work is about agency. Reframing the past in the contemporary world, he creates nuanced spaces and shows how mutable the notions of authenticity and historical norms really are.

In Teen Venus, he depicts his subject in a moment of transition between childhood and adulthood and in a hybrid space suspended between sea, beach and sky. His portrayal of her is not quite of this world. He knows that the sinuous curves of her contrapposto stance links her back to an older artistic tradition, that of ancient Greek sculpture and its illusion of movement through the apparent shifting of weight between a bent and straight leg. He also knows that this pose, the gentle tilt of her head and her luxurious flowing hair recalls Sandro Botticelli’s painting The Birth of Venus from the mid-1480s. In Botticelli’s work, the new-born goddess stands nude on a giant scallop shell as she emerges, fully grown, from the sea. In it, Botticelli was playing a game of artistic appropriation. By the end of the 15th century, European audiences would not have seen a large standing female nude as the central element in a work of art since the times of the Romans, some ten centuries previous. Botticelli’s pictorial composition was quite simply unprecedented in its time. And his debt to classical art goes further than that. His figure’s stance with her hands covering her breast and pubis is based on a famous type of sculpture from Antiquity: the Venus Pudica, the Venus of Modesty. By these references, Botticelli demonstrated his understanding and engagement with the cutting edge of cultural of his time. The rediscovery of artworks from the ancient world was the excitement of his age. By updating these classical forms, he remade and reactivated an older tradition for an audience of his peers. His work affirms both his public’s erudition and their progress as they looked to the future.

So Erizku’s photography stands firmly within this centuries-long dialogue about the ability of older forms to take on new meaning and speak to new audiences. However, Erizku’s work, by raising the question of who gets to be seen and celebrated in art, heightens that conversation. This is more than a game of reference and counter-reference. This is a challenge to centuries of iconography and interpretation that has ignored and marginalized generations of people of color. His work asks us to look again, see the absences and ask ourselves why we did not look for them before. All of this may be a lot to place on the lovely shoulders of our Teen Venus, but her look is undaunted. She knows what she represents. She understands her place in this discussion about history, beauty, and belonging. This is her stretch of beach and the power of the waves behind her seem at her beck and call. She is asking about our trespass into her realm and her look defines us as the outsider. Too often we forget that the goddess Venus was more than a pretty face and sensuous figure. Time and time again, she proved herself to be more than willing to seek violent and bloody retribution against mortals of both sexes who angered her. You ignored or disparaged her at your peril.

Like her namesake, and despite her young age, Erizku’s Teen Venus is not one to be trifled with. She is looking. She is watching. She is seeing.

– Sara Cochran

Reflection On The Body In Art and Dance

After Martha Graham Dance Company's residency at The Church in February, 2021, Eric Fischl offered this reflection on their work and the state of the body in art.

After Martha Graham Dance Company's residency at The Church in February, 2021, Eric Fischl offered this reflection on their work and the state of the body in art.

To see people using the space of The Church creatively, as intended, since only having workers there or bringing the occasional curious supporter through has made all the difference to me. The Church has now come to life with the residency of the Martha Graham Dance company, has begun to do what it was meant to do. The choreographers and dancers loved being and working there, and we were honored to have them inaugurate the space.

It was amazing to watch choreographer Sonya Tayeh transmit her vision and see the dancers (Lorenzo Pagano, Leslie Andrea William and Jacob Larsen) realize it! I felt privileged being allowed to witness her creative process, making the most subtle adjustments (how deep a dancer’s shoulder must turn, how sharp a cut, how long the position is held) are the seemingly small things you think you wouldn’t be able to perceive until you experience those refinements in creation and realize how big a difference they really do make.

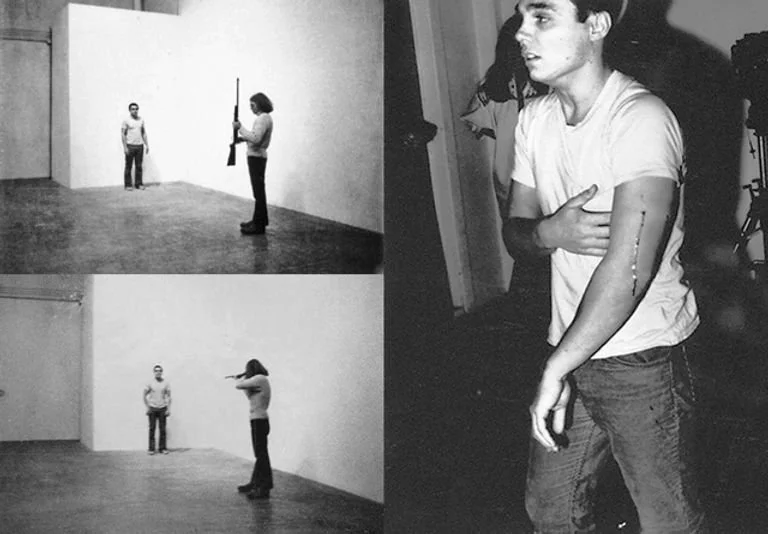

I was talking to Janet Eilber, the artistic director of the Company about the body in dance and it reignited a meditation I have long had on the disappearance of the body in 20th century visual art. Here is a brief historic trajectory through Auguste Rodin, Alberto Giacometti, Vincent van Gogh and Chris Burden.

Rodin was the ultimate believer in our body’s ability to express itself, to externalize the emotional, sexual, psychological and spiritual needs of our souls. No matter how fragmented his sculptures are (sometimes only a hand, a foot), you know immediately and empathetically what the rest of the body is feeling.

Post WWII, the great Modernist sculptor Giacometti’s bodies are emaciated, chewed up figures who show the soul no longer being able to externalize, to share its angst except through deprivation. His artistic vision is the anorectic condition, the body barely animate.

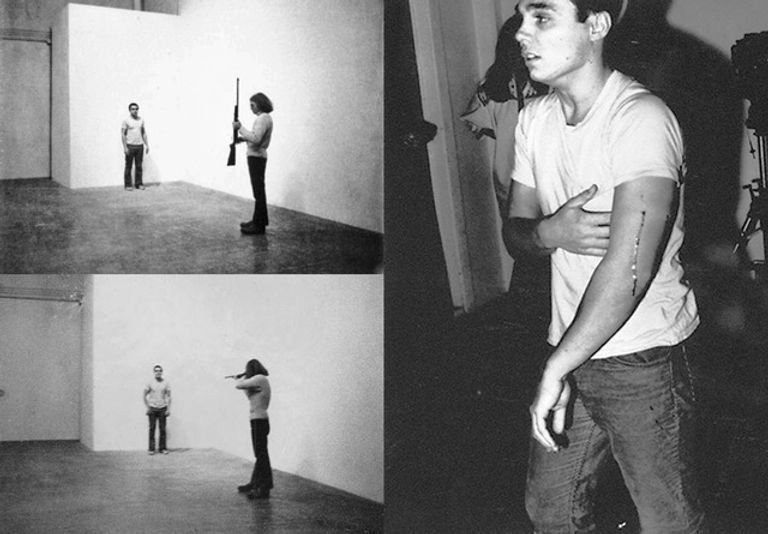

In 1888, Van Gogh, in distress, cuts off his ear. No one thinks that was a work of art. He made a painting called Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear. Everyone thinks this is art.

Almost one hundred years later, the radical body artist Chris Burden has himself shot in the arm as a performance at an art gallery. Everyone thinks this is art.

What happened in those 100 years that we would come to embrace self-mutilation as a form of creative expression? Aren't our struggles with injustice, helplessness, disappointments, missed opportunities, longing for connection and pleasure the same as they have always been? Certainly, it isn’t the body that has changed. So, what has changed?

This ongoing meditation was reactivated this week while watching these extraordinary dancers use their bodies in such expressive and beautiful ways. The one thing that cannot be disputed is that without the body there would be no dance. And watching them move in space as art, as expression, was a truly healing experience, inspiring and emotionally intact. It was also proof of a great artistic tradition that endures in the Martha Graham Dance Company.

– Eric Fischl, February, 2021

Short videos of the rehearsals are available on our YouTube Channel at The Church Sag Harbor